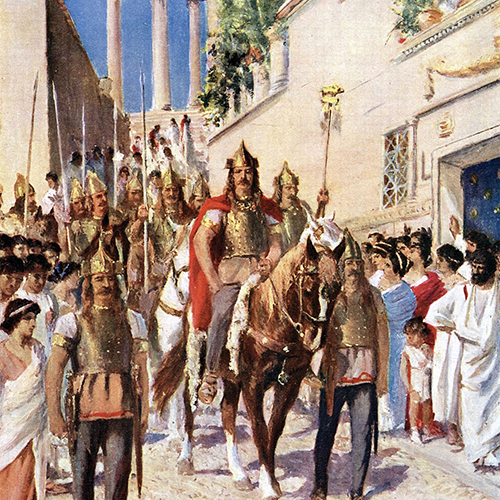

Alaric entering Athens by Allan Stewart, ca. 1920

At its peak, the Roman empire extended from Britain to the Sahara Desert, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Euphrates River. Yet in 476, the last western Roman emperor was deposed. Imperial authority survived in the east, centered in the city of Constantinople, but the western regions were divided between Germanic kingdoms and the rising influence of the papacy. Historian David Gwynn analyzes the dramatic events which shaped the decline and fall of the Roman empire in the west, exploring the transformation from the ancient to the medieval world that laid the foundations for modern Europe.

Gwynn is an associate professor in ancient and late antique history at Royal Holloway in the University of London and the author of The Goths: Lost Civilizations and Christianity in the Later Roman Empire: A Sourcebook.

April 9 Imperial Power and Christian Triumph

The fourth century was a time of rapid change for the Roman empire, which had dominated the Mediterranean world for more than 300 years. Imperial persecution of Christianity was replaced by active support under the emperor Constantine and his successors, while the establishment of Constantinople created a new center of power in the east. Gwynn examines the strengths and weaknesses of the fourth-century Roman empire, from the social and religious developments that influenced later generations to the shifting pressures on the frontiers that heralded the beginning of the Germanic migrations into Roman Europe.

April 16 Goths, Huns, and Vandals

In the summer of 376, an estimated 100,000 Gothic men, women, and children descended upon the Roman empire’s Danube River frontier. They came as refugees not invaders, fleeing the advance of the nomadic Huns, and their arrival set in motion the complex train of events that culminated in the collapse of Roman power in the west. Gwynn offers a wide-ranging account, from the Goths under Alaric who sacked Rome and the Hun empire of Attila to the Vandal conquest of North Africa and the abandonment of Roman Britain, ending with the deposition of emperor Romulus Augustulus and the disappearance of the western Roman empire.

April 23 The Rome that Did Not Fall

The last western Roman emperor was deposed in 476. In the east, however, imperial control endured, and any attempt to explain the collapse of Roman power in the west must also explain the survival of the eastern empire. The emperors ruling in fifth-century Constantinople faced political and religious divisions which had lasting consequences for Christianity, as well as threats from Goths, Huns, and Persians. Gwynn examines how the eastern emperors from Theodosius I onward preserved their authority and so made possible the attempted western reconquest under Justinian in the sixth century and the emergence of what is known as the Byzantine empire.

April 30 Barbarian Kings and Roman Popes

By 500, the western Roman empire had been replaced by a mosaic of Germanic kingdoms. Gwynn charts the contrasting fortunes of the Gothic kings in Italy and Spain, Vandal North Africa, and the Franks in Gaul who alone succeeded in establishing the basis for a modern country. All these kingdoms preserved Roman culture to varying degrees, with Anglo-Saxon England the notable exception, and their fates helped to shape medieval history. Yet only the bishops of Rome still possessed influence that extended throughout the former empire, and the rise of the papacy symbolized a Europe united not politically but through the shared faith of Christendom.

4 sessions

General Information