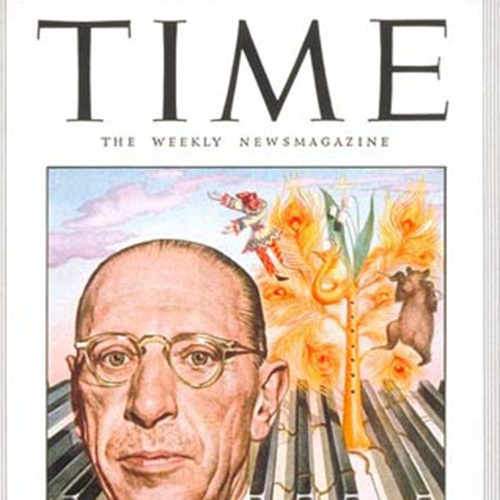

Illustration of Igor Stravinsky, Time magazine cover, 1948

Beethoven never made it to America, but hundreds of important musicians and composers did. From early touring megastars like Paderewski—who traveled in his own private Pullman car—to successful refugee émigrés such as Rachmaninoff, America has been drawing renowned musical talents since well before its Declaration of Independence. Dvorák directed a music conservatory in New York; Korngold wrote scores for Hollywood; Tchaikovsky marveled at the warmth of American hospitality; and Schoenberg played tennis regularly with Gershwin.

In a unique course, popular speaker and concert pianist Rachel Franklin explores the siren call of America to musicians throughout the world.

British-born Franklin has been a featured speaker for organizations including the Library of Congress and NPR, exploring intersections among classical and jazz music, film scores, and the fine arts.

March 9 Beethoven Arrives

Beethoven’s music made its American debut in an 1805 concert in Charleston, South Carolina, but the composer wasn’t there to enjoy it and never had the chance to visit the United States. Nonetheless, Beethoven’s revolutionary style of music and his evolution as an artistic icon would go on to permeate every aspect of American culture. As musical societies were springing up everywhere, Beethoven became the bust of choice on every music-lover’s mantelpiece. Works include the composer’s First Symphony, plus music by Thomas Jefferson, Charles Theodore Pachelbel, and delightful ballades, jigs, and emigration songs of the period.

March 16 Traveling Virtuosi

Adelina Patti and Anton Rubinstein, Old Arpeggio and the Swedish Nightingale: Franklin dives into the entertaining mix of hucksterism and high art that characterizes 19th-century American musical entertainment as she follows various traveling virtuosi across the country as they astonish and captivate their audiences. While much of their earlier repertory has vanished forever from concert programs, these intrepid performers helped to glamorize classical music and laid solid foundations for the more discerning listeners of the future. Works include music by Gottschalk, Wieniawski, and Paderewski.

March 23 Building Legacies

Many mighty European musicians and composers helped to build the greatest institutions of American musical life. Gustav Mahler served as the tenth music director of the New York Philharmonic; Serge Koussevitzky was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra; Antonin Dvorák directed the National Conservatory of Music in New York City; Leopold Stokowski served as artistic director of the Philadelphia Orchestra and appeared in Disney’s Fantasia. Franklin reviews the significant contributions of European composers to musical life in America and how they continue to shape our cultural world today. Works featured include Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony and excerpts from the score of Fantasia, plus archival media of Toscanini and other early stars of the American classical music stage.

March 30 Émigrés in America

In the early 20th century, Europe experienced a mass exodus of artists and musicians escaping the horrors of Soviet oppression and Nazi persecution. Among them were some of the greatest composers of their time— Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Korngold, Bartók, Milhaud, Schoenberg, and many others. Some of these composers struggled in a new world while others built brilliant new careers here. Each of them shared their genius with America and left an indelible mark on an evolving culture that welcomed and absorbed their great gifts. Works featured include excerpts from Korngold’s film scores, Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, Stravinsky’s Ebony Concerto written for Benny Goodman, and music by Rachmaninoff, Kurt Weill, and others.

4 sessions

General Information